As in Part Four, where we looked at ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’, containment in an interior was similarly critical to Charlotte Salomon, a young Jewish art student from Berlin who hid from the Nazis in house in the south of France during the Occupation.

Charlotte Salomon

Self Portrait 1940 Jewish Museum Amsterdam

Salomon produced her major work Life or Theatre? under incredibly difficult conditions. As a consequence of the trauma of the Holocaust, and also because of the work’s explosive contents, this work was hidden from the public for years until its first exhibition in Amsterdam in 1961.

Charlotte Salomon grew up in Berlin. In 1939 she was sent by her worried parents to stay with her maternal grandparents in the South of France where they were already settled in Villefranche-sur-Mer, near Nice. Charlotte took with her nothing but a tennis racquet, some records and a small suitcase.

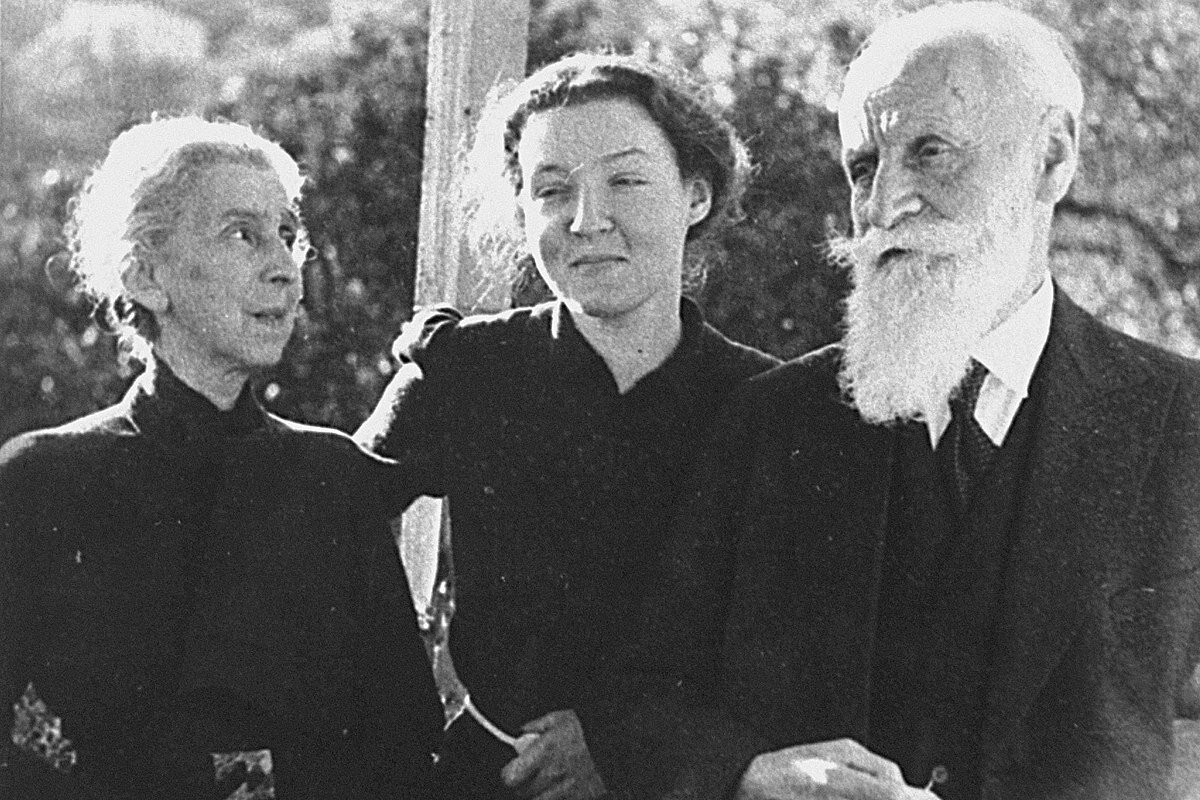

Salomon and her grandparents, Doktor and Mrs Lüdwig Grünwald

When she was only eight Charlotte had lost her mother to suicide. In 1939 during the first year of her stay her grandmother committed suicide as well. This prompted an impromptu confession from her grandfather that her aunt Franziska and her own mother had taken their lives, as well as several other family members.

Not only did Charlotte have this information to deal with, she had been briefly interned by the Nazis, along with her grandfather, but released due to his poor health. A cold and highly manipulative man, her grandfather was also constantly attempting to share her bed.

She said at this point she would either ‘end her life’ (like her mother, aunt and grandmother had) or she would undertake 'something really extravagantly crazy'.

Furious, disgusted and in fear of her life, Charlotte decided to let all the lies and untruths out of the family closets through a frenzied production of 1350 odd gouache paintings with cellulose overlays, over the course of one year. Edited down, these make up Life or Theatre?

In the summer of 1942 and determined to complete this project without interruption, she rented a room in a pension, la Belle Aurore in St. Jean Cap Ferrat, Here, cut off from everything she laboured intensely with paints and overlay, often humming to herself as she worked.

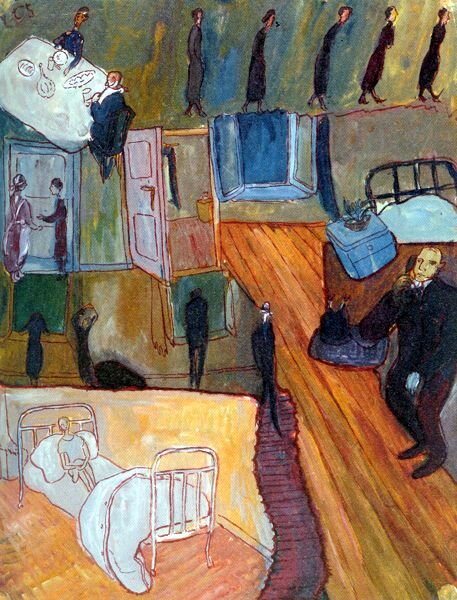

From Life or Theatre?

In an outpouring of immense scale she painted her life's story, giving the main characters alternative names. In 1943, as the Nazis intensified their search for Jews living in the South of France, and just before she was deported to Drancy, and then Auschwitz on 7 October, she gave the entire project to a non-Jewish friend known only as Dr Moridis. "Keep it safe," she told him. "It is my whole life."

Life or Theatre? features an extraordinarily inventive pictorial language, which draws on contemporary cinema and music, as well as on her training in modern art in Berlin. Taken together, the work was intended to be a singespiel, a play with music: Salomon indicated the accompanying songs on the back of the drawings or on transparent overlays.

Through these means Charlotte tells the tragic tale of suicides, and finally murder, in her family. The paintings show not only what happened, but also how she feels about these events. It’s a fearless engagement, which is far from comforting.

In individual images she was very much before her time in her use of an almost graphic novel structure. These also suggest the story-boarding technique that film directors use. Salomon also incorporated ‘cinematic’ framing and composition.

The interiors we see are sieved through memory, rendered as much for how they felt to occupy as for what scenes they illustrate yet there are critical to our understanding. The interiors areboth ‘real’ yet theatrical, they are the spaces of trauma re-imagined and re-constructed while Charlotte herself was in hiding.

Here for example below we see this remarkable rendering of the family apartment in Berlin from an aerial viewpoint.

Her family were wealthy, and their apartment most likely occupied two floors, which is why windows in the bedrooms don’t make much programmatic logic. Even so it’s almost as if we looking down into an architectural model, or a doll’s house with hinged roof that opens.

The perspective is dizzying, but the details are intensely accurate. Tiny figures occupy some of the rooms, in the kitchen we see ‘Augusta the cook, sitting and waiting for orders’. The apartment, so the accompanying text goes was ‘truly beautiful’, and she has rendered the drawing room, which her mother used as a music room, and intense vivid blue.

“Thank God she is not yet dead”.

Above is another important interior in the series that shows the bathroom of her grandparents near Nice. The text for this image is ‘She [Charlotte’s grandmother] tried to kill herself. “Thank God she is not yet dead”. This attempt would be repeated, this time successfully, not long afterwards. On this occasion Charlotte’s grandmother had taken poison.

The composition with its high angle view point and cropped edges, invokes the mechanical eye of the camera, rather than the wider view of the human eye. Perspective is skewed, and we glimpse what looks like a rolled up part of a pressed metal ceiling, or even an internal gallery corridor.

Charlotte herself is the tall blue figure, and bending creepily over the scene is grandfather, with what looks like either the tip of a mustache wing, or a smirk on his face. The words, in vivid red, seem to hover between the pictorial surface and the back wall of the bathroom itself, upon which they might almost have been graffittied.

In October 1943, at the age of 26, Charlotte Salomon was killed in Auschwitz. She was five months pregnant, and had just married to Alexander Nagler.

To view the entire work please click on the link below which will take you to the Jewish Museum Amsterdam: they have also included the prescribed sound track for each image as noted by Salomon on the back of each work.

https://charlotte.jck.nl/section

Thus as we’ve explored in Parts Four and Five, with ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ and here with ‘Life or Theatre?’ two significant women, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Charlotte Salomon, ‘took over’ the lock-down script and change it from within using the situation of being cut-off to work in deep, intense and concentrated ways.

Georgina Downey is an art historian and Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Adelaide who has published widely on the domestic interior in art. She has received an Australian Academy of the Humanities Travel Grant (2006) and University of Adelaide small research grants. Her most recent books are Domestic Interiors: Representing Home from the Victorians to the Moderns, (2013) and Designing the French Interior: The Modern Home and Mass Media (edited with Anca Lasc and Mark Taylor 2015) both published by Bloomsbury. Her next project is a co-edited anthology with Mark Taylor and Terry Meade Domesticity Under Siege: when home isn’t safe to be published by Bloomsbury in 2021.